Using Transkribus to Find Privacy in Plakkaatboeken, Mandatenbücher and Policeybücher from the 17th century

HTR, KWS and Fuzzy Searches within Police Ordinances

Abstract

Early modern texts are notorious for their handwriting, or indeed, their Gothic fonts in print. A tool that allows easing the process of making transcriptions is much welcomed, and this is where Transkribus comes in. In my research, I use Transkribus to deal with legal sources from the gewesten of the Low Countries and canton Berne (CH), stemming from books of ordinances (plakkaatboeken) and Mandatenbücher and Policeybücher. (Police) Ordinances and mandates are early modern normative texts that guided society.1 They cannot be described as laws, as they were not necessarily top-down imposed but could also result from traditions and everyday practices that became regulated. These rules can be found throughout Europe. They give an excellent overview of the judicial framework of society, and thus, form an excellent source to study privacy.

In this article, I focus on the question: how can Transkribus’ findings support an in-depth understanding of historical sources on privacy? I will verify whether themes about privacy can be found in the three corpora that I focus on in my current research, namely books of ordinances (plakkaatboeken) and Mandatenbücher and Policeybücher from mainly the 17^th^ century, from the Low Countries, on the one hand, and from the canton Berne, in what today is Switzerland. In the article “Spaces of Privacy in Early Modern Dutch Egodocuments,” Michaël Green argues that the word privacy, meaning ‘regulating access to oneself and to one’s material or immaterial resources’ was not yet used in egodocuments in the context of the Dutch Republic, despite the existence of some (early) hints. Do Green’s findings hold for my corpora, too? Since my primary sources are predominantly handwritten, I will demonstrate how providing the ability to quickly perform Keyword Spotting (KWS) and Fuzzy Searches makes Transkribus an efficient tool for this question.

The European Union (EU) funded a two-year project called TranScriptorium, which aimed to create “innovative, cost-effective solutions for the indexing, searches and full transcription of historical handwritten document images, using modern, holistic HTR tech.”2 TranScriptorium was succeeded by Recognition and Enrichment of Archival Documents (READ), funded by the EU Horizon 2020.3 The READ-project resulted in a platform and tool called Transkribus, which eases transcribing texts and allows for the training of Handwriting Text Recognition (HTR) models to make automatic transcriptions. Since 1 July 2019, when the EU grant ended, Transkribus became a paid service under the READ-COOP that maintains and further develops the platform. Although the University of Innsbruckwith Günter Mühlberger is the platform coordinator, universities throughout Europe participate(d) in the development.4 Transkribus has different Graphic User Interfaces (GUIs) for different purposes and users. It has an Application Programming Interface (API) for programmers that run bulk amounts of documents; it has an Expert Client with the same options as the API to process individual documents for frequent users; and it has an online Lite-environment with far fewer options that needs no Javascript. The latter is often used by crowdsourced projects when the main task is to solely make transcriptions or add metadata-tags without applying advanced Layout Analysis (LA). Transkribus Lite is still much under development, whereas the API and the Expert Client are much more advanced in their development and have a wide array of options.

As this contribution is centred around methodology, I explain how I can use Transkribus Expert Client in my research about privacy in ordinance documents.5 I will start at the point where you train an HTR model, which options there are, and then how to run a model over new images. Consequently, I explain how Keyword Spotting (KWS) and Fuzzy Searches within Transkribus are advanced tools that helped me to find evidence to answer my research questions.

Working with Transkribus: Creating Models and Automatically Transcribed Texts

Transkribus does not read texts, but after a certain amount of training, it can recognize and decipher characters given that it knows where the text regions are located. The training pages allow Transkribus to match ‘squiggly things’ to the characters indicated by the user in the transcription field. The minimum amount of training data is about 1000 lines, roughly about 30 pages written in one hand.6 The more pages of training material, the better the results generally are. At the servers in Innsbruck, where all images and data are stored, the AI techniques will calculate probabilities of which character is likely to be prior or follow another character. E.g. a ‘q’ is nearly always followed by a ‘u’; Thus, when a ‘q’ is found in the text the probability of an ‘u’ following suit is very high.

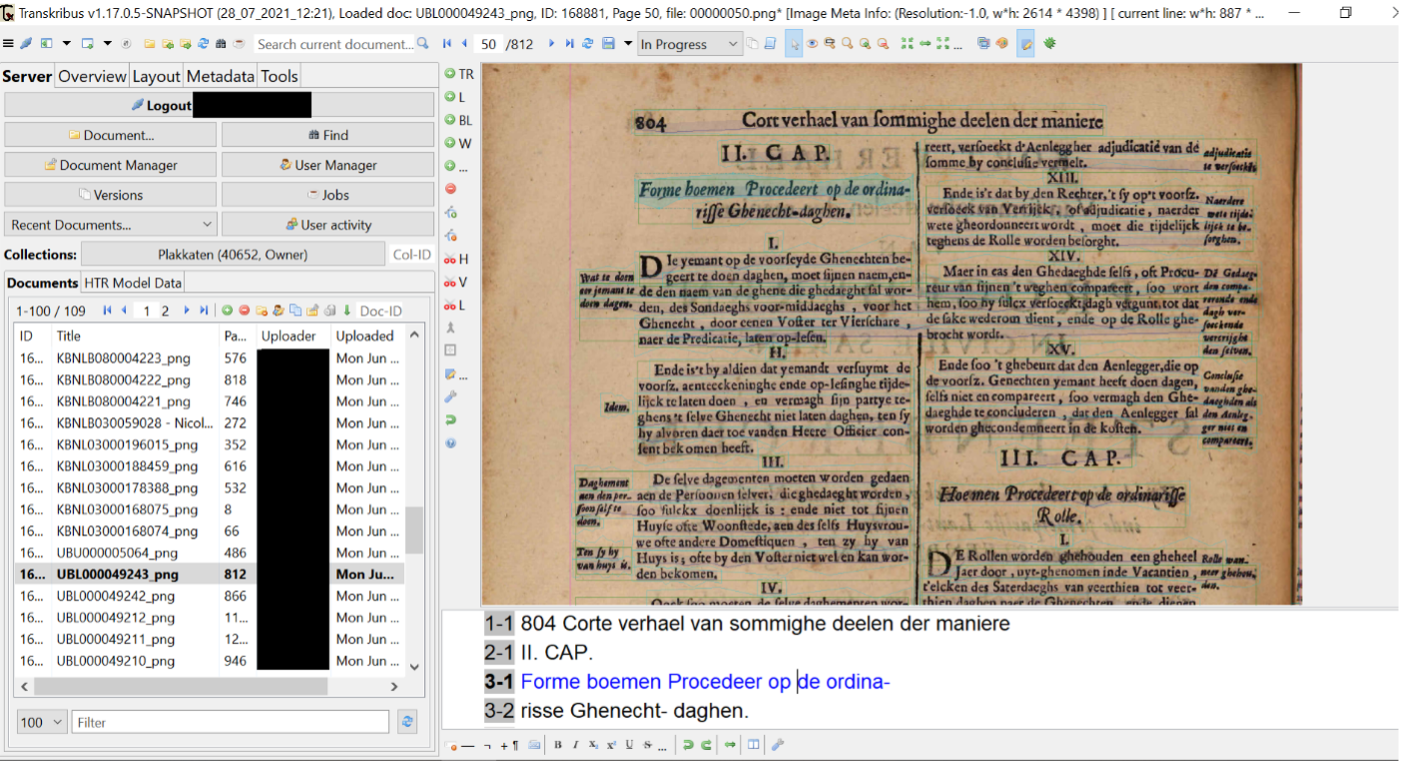

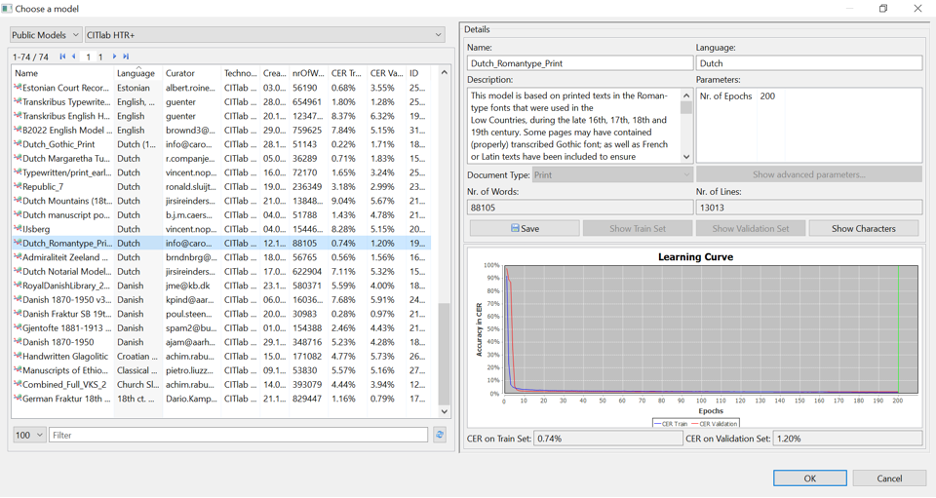

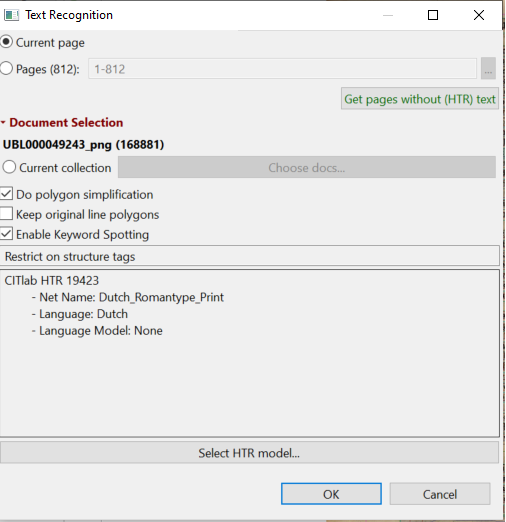

When the minimum amount of manually transcribed texts has been reached, a training button is needed to train a model in the Toolstab.7 Let us briefly look at the various options within the Tools-tab. The first tool that is found here, is the automatic layout analysis. You can opt for either processing your document in its entirety,a selection of pages, or,if you drew manual Text Regions, only the lines withinthe Text Regions. If you would like to apply automatic LA on several documents, you can do so by selecting this in the Document Selection tool. Next, the Text Recognition tool is listed. As you can see in Image 2, this tool shows two methods for HTR: CITlab HTR+ and PyLaia; the dropdown menu also shows Transkribus OCR. Text Recognition has two buttons: Models, showing available (public) models within your collection, and Train, to create your own models. Furthermore, the button Run activates readily available models for your text.

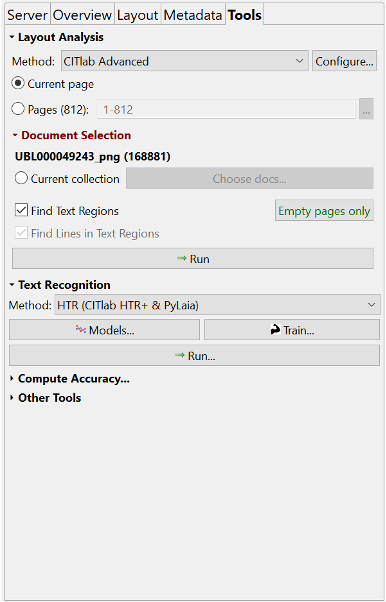

When you want to train your own model, based on the minimum of 30 pages you manually transcribed, you click on the Train button.

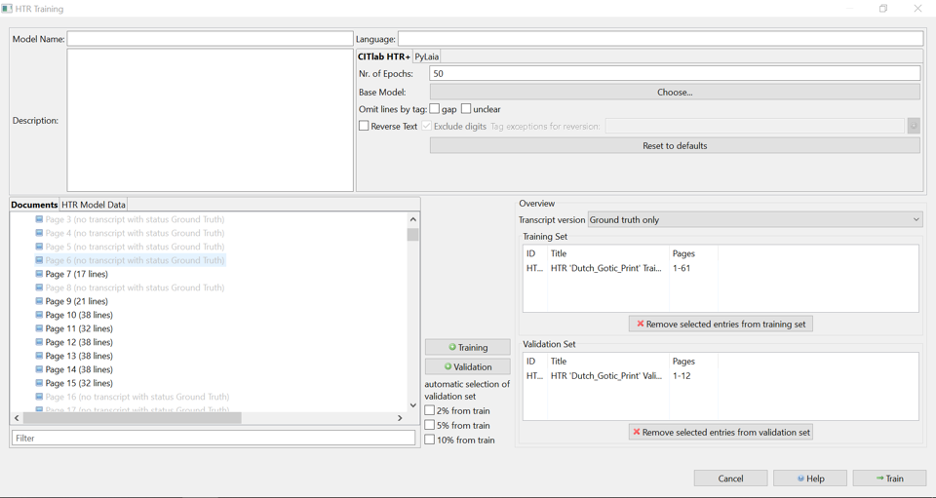

Good models consist of a minimum of 1000 lines, 90% of the pages are to be assigned to Training Set, and 10% must be labelled as a Validation Set. You can opt for a lower percentage, but then you need to ensure that it is representative for the texts given, or it needs to be an exceptionally large dataset. When you click on Train, a screen opens providing numbers regarding words and lines that have been selected. For proper models you need a minimum of 1000 lines. Training a model can take several hours, but you will receive a notification in your email when your model is ready. Your model can then be found in the Toolstab > Text Recognition > Models. Here you also find a graph that shows how well your model performs on your data and an estimate how it functions on unseen text. This is expressed in a percentage of Character Error Rate (CER). Depending on the score, you might want to train additional pages.

The blue line in the model’s graph indicates how well the computer learned from the provided training data; the red line is the ‘unseen’ dataset (validation set). Models that have a CER > 10% are quite readable, but it is advisable to try to get at least between 7-5% CER with handwritten texts. Printed texts can come close to a 1% CER. It is preferred that the blue and red lines come close to each other, as that demonstrates that the model functions properly. When you are satisfied with the outcome, you can run the model over new pages of the same hand or similar font.

When you run your model, you will have to decide whether you test it on a single (current) page or run it on the entire document or only on the pages that have not yet had transcripts. Do realize that, when you run your model, this is the only moment you can decide to Enable Keyword Spotting, which requires an extra action on the servers in Innsbruck as it needs to form a confidence matrix per word to go with your document(s). As this costs a lot of storage space and time, you need to consider whether you need this. If you do not do this straight away, you cannot use the Keyword Spotting option later without needing to run a model anew over your document.

Analysing Data with Transkribus: Search Options

In the earlier section, I discussed the basics to use Transkribus and how to get ready to transcribe, make a model and run the model on your text. In this section, I will explain several options within the platform to search for terms within the text: Full-text and Fuzzy Search (SOLR8) and Keyword Spotting.

Full-text and Fuzzy Searches

The better the HTR-results, the easier full-text searching becomes. Especially with printed texts, exact phrases can easily be found through the SOLR Full-text search. As I have explained above, Transkribus works with probabilities in character combinations. Fuzzy searches show more possible outcomes considering misspelled or ill-transcribed words. While the word ‘privacy’ was not yet in use in the early modern period, a fuzzy search of the term reveals a full range of related priv*-words.9

To search for words in texts you need to click on the binoculars’ button on the top toolbar. A screen opens with four different tabs to search: Documents, Full-text (SOLR), Tags, KWS. With Documents, you can search within your collection based on features that have been manually displayed in the document properties. This is particularly convenient if you work with substantial amounts of text. Tags allows you to search e.g. structural tags (when used) such as titles, paragraphs or specifically designed tags.

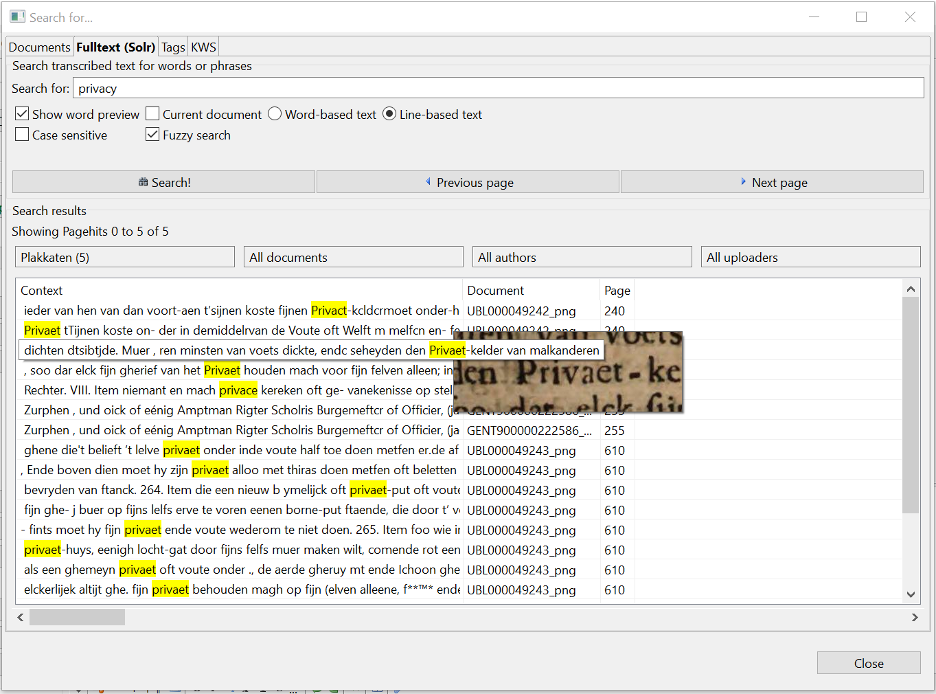

With Full-text, you can decide whether you want the computer to look at individual words, or at the line-based texts, whether you want to search Case sensitive or indeed Fuzzy search. You can narrow the search down to a single collection, all documents or specific authors as illustrated in image 6. When you hit Search! the results will appear in the search field, showing the context, the document number, and which page the results were found. When you hover your arrow over the text, you will be shown a small image of how the word looks. With these previews, you can determine whether the word has been correctly identified as the one you were searching for. Keep in mind that with Full-text search the searches are performed on the textual output and will not function on pages that have not been transcribed or have very bad transcriptions.

Keyword Spotting (KWS)

As indicated above, when you want to keep the option to use KWS you will need to activate this when you run a model over your texts.10 The servers in Innsbruck will need to store confidence matrices per word while running a selected model. These are based on the HTR model that you run on your text, assigning each character a value of how certain it is that the character is a particular letter. In other words, it calculates the probability per character and the highest outcomes are produced as a string of characters making up a word which is sometimes correct and sometimes not. Hence, machine-made transcriptions are not 100% correct, nor will they necessarily produce the same outcome when you run a model twice. Even if a model is not good (>7% CER) you can still try KWS as it works on the stored matrices on the servers, not on the transcriptions.

You can search with Partial Matches, Case-sensitivity, or an Expert Syntax. The latter allows you to look for regular expressions without having to program. You can also search for the combination of two or more words. When you look for a particular word, such as in the example of Image Seven ‘Privaet,’ you will get the results listed based on the confidence matrices. The highest score is found at the top of the list, showing the line transcription and a preview of the word. Here, the preview also gives you an indication of the context in which the word was found.

![KWS on *Privaet* in Michiel Knobbaert, *Brabandts Recht

[...]* (Antwerpen, 1681).](https://dev.crdh.rrchnm.org/assets/img/v07/romein/figure7.png)

Concluding: Analysis of the finds

While you are still developing your programming skills, the options described above are helpful. You can work with vast amounts of handwritten or printed material, make them machine-readable and searchable for not only the words, but also the context.11 This section will analyse the findings that Transkribus provided for both the Dutch and Swiss sources.

Searching through 107 Plakkaatboeken (books of ordinances) could be tedious. Yet, a quick search through all the documents automatically transcribed in Transkribus exponentially increases efficiency. The word privé turns up 1541 hits, but these are either misfits or within a particular context: the Conseil Privé or secret council. When looking for priva*, the total number of finds is 1709, which may contain several misfits. Browsing through an example from 1716 the mentioning of ‘privatelyk’ turns up in an interesting context: no foreign interference with private issues (privatelyk) including religion, police, finance or justiceof the Republic.12 Other references to privat*/priva* to have a meaning of deprivation (withdrawal) of a title13 or office, to ‘private Persoonen’ (private persons/ individuals)14 or private law. These findings do support Michaël Green’s conclusion that the word privacy, defined as ‘regulating access to oneself and to one’s material or immaterial resources’ was not yet used, despite some early hints.15

The Bernese normative texts in the 41 Mandatenbücher cover the period 1528 until 1789, the 26 Polizeibücher start in 1458. Transkribus picks up 59 mentions of the word Privat and 138 times Priva* within this timeframe. When going through these results, it becomes clear that by far, most cases have a reference to ‘privat sachen,’16to contrast public affairs.17 It is also used to indicate ‘in privat Häuseren’18 (private houses). ‘privat hand’19 (possession of an individual), and for private goods. The word seems to make a clear distinction between what is a public affair, or what belongs to an individual or touches upon an individual’s interest. In 1684, a Jeremias Sterchis was appointed to the Philosophische Theoretischen Preffession in Bern, his qualities were summed up as well as the topics he previously taught. It is also mentioned that his private Institutiones should be acknowledged.20 Heide Wunder points out that the term for privacy would be Privatheit, which is absent from both corpora.21 Wunder remarks that private is often merely used as the opposite to public, which is in line with the Bernese findings. These Latin-derived terms become clear in the handwriting too, where the difference between Fraktur and Antiqua is visually evident due to the biscriptality or script-switching.22S

These matches show that a researcher can now quickly find the entries and then focus in-depth on the context rather than deciphering the handwriting to find such entries. Moreover, if, based upon the context, another term or synonym proves to be helpful to investigate further, it is just as easy to search for that term.

Bibliography

Green, Michaël. ‘Spaces of Privacy in Early Modern Dutch Egodocuments’. TSEG - The Low Countries Journal of Social and Economic History 18, no. 3 (29 November 2021): 17–40. https://doi.org/10.52024/tseg.11041.

READ-COOP. ‘How To Search Documents with the Keyword Spotting Feature’. Accessed 3 August 2021. https://readcoop.eu/transkribus/howto/how-to-use-keyword-spotting/.

Kaislaniemi, Samuli. ‘Code-Switching, Script-Switching, and Typeface-Switching in Early Modern English Manuscript Letters and Printed Tracts’. In Verbal and Visual Communication in Early English Texts, 37:165–200. Utrecht Studies in Medieval Literacy 37. Brepols Publishers, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1484/M.USML-EB.5.114135.

Muehlberger, Guenter, Louise Seaward, Melissa Terras, Sofia Ares Oliveira, Vicente Bosch, Maximilian Bryan, Sebastian Colutto, Hervé Déjean, Markus Diem, and Stefan Fiel. ‘Transforming Scholarship in the Archives through Handwritten Text Recognition’. Journal of Documentation 75, no. 5 (2019): 954–76.

‘Recognition and Enrichment of Archival Documents | READ Project | H2020 | CORDIS | European Commission’. Accessed 29 July 2021. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/674943.

Romein, C. Annemieke, Max Kemman, Julie M. Birkholz, James Baker, Michel De Gruijter, Albert Meroño-Peñuela, Thorsten Ries, Ruben Ros, and Stefania Scagliola. ‘State of the Field: Digital History’. History 105, no. 365 (2020): 291–312. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-229X.12969.

Romein, Christel Annemieke, Sara Veldhoen, and Michel de Gruijter. ‘The Datafication of Early Modern Ordinances’, DH Benelux Journal, 2 (2020). http://journal.dhbenelux.org/journal/issues/002/article-23-romein/article-23-romein.pdf.

‘TranScriptorium | TranScriptorium Project | FP7 | CORDIS | European Commission’. Accessed 29 July 2021. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/600707.

Wunder, Heide. ‘Considering “Privacy” and Gender in Early Modern German-Speaking Countries’. Early Modern Privacy, 9 December 2021, 63–78. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004153073_004.

-

Romein, Veldhoen, and de Gruijter, ‘The Datafication of Early Modern Ordinances’. ↩

-

‘TranScriptorium | TranScriptorium Project | FP7 | CORDIS | European Commission’. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/600707 ↩

-

‘Recognition and Enrichment of Archival Documents | READ Project | H2020 | CORDIS | European Commission’. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/674943. ↩

-

Muehlberger et al., ‘Transforming Scholarship in the Archives through Handwritten Text Recognition’. ↩

-

If the reader is interested to learn the basic steps of uploading images and transcribing a couple of pages of text, there are three webinars available on YouTube: C.A. Romein (2020), Transkribus webinar (basic): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5YCfaFNMol4; C.A. Romein (2020), Transkribus Webinar #2 – Advanced Use: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yxLyzRZaff8; C.A. Romein (2021), Transkribus Webinar #3 -Pylaia and updates: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=axYRvhgcVF4. ↩

-

If a text is manually corrected and reaches (near) perfection, it may be labelled as Ground Truth. ↩

-

The Trainings button can be requested (for free) through: info@readcoop.eu. ↩

-

Solr stands for: Searching On Lucene w/ Replication. ↩

-

Bruun, ‘Towards an Approach to Early Modern Privacy’ (https://brill.com/view/book/edcoll/9789004153073/BP000012.xml ). ↩

-

See for the Transkribus digital manual on KWS: ‘How To Search Documents with the Keyword Spotting Feature’. ↩

-

See: ‘How To Search Documents with the Keyword Spotting Feature’. ↩

-

‘Resolutie van de Staaten van Holland, inhoudende verscheide schikkingen nopens ‘t geval, dat haare Koninklijke Hoogheid geduurende de minderjarigheid van den Heer Prince Erfstadhouder, of van de Princesse Carolina mogte overlyden. Den 10 February 1752’, in: D. Lulius and J. van der Linden, Groot Placaatboek vervattende de Placaaten, ordonnantien en Edicten van de Hoog Mog. Heeren Staaten Generaal, Agtste deel (Amsterdam 1795), 149: XI. ↩

-

8 May 1664 in: Recueil Chronologique de Tous Les Placards, édits, décrets, réglemens, ordonnances, instructions et traités (Brussels, 1785) : Tabel des Matieres : 9. ↩

-

Joyous entry 26 April 1515, J. Baptiste Christyn, Brabandts Recht, dat is Generale Costumen (Antwerpen, 1682) 1238 ↩

-

Green, ‘Spaces of Privacy in Early Modern Dutch Egodocuments’, 17–18. ↩

-

StAB, Kanzleiarchiv (A) Verfassung und Gesetzgebung (1218-1919) I – Mandatenbücher (1528-1798) 490 p. 589 (25 June 1701). ↩

-

StAB A I 490 p 396 (21 November 1698). ↩

-

StAB A I Polizeibücher (1470-1798) 461, p. 458 (5 December 1687). ↩

-

StAB A I 460, p. 310 (22 August 1665). ↩

-

StAB A I 461, 393-394 (7 February 1684). ↩

-

Wunder, ‘Considering “Privacy” and Gender in Early Modern German-Speaking Countries’. ↩

-

Kaislaniemi, ‘Code-Switching, Script-Switching, and Typeface-Switching in Early Modern English Manuscript Letters and Printed Tracts’. ↩

Author

Annemieke Romein,

Department of History, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, c.a.romein@utwente.nl,